NUTRIA EXHIBITION OPENING ARTICLE

by Lyndall Cain

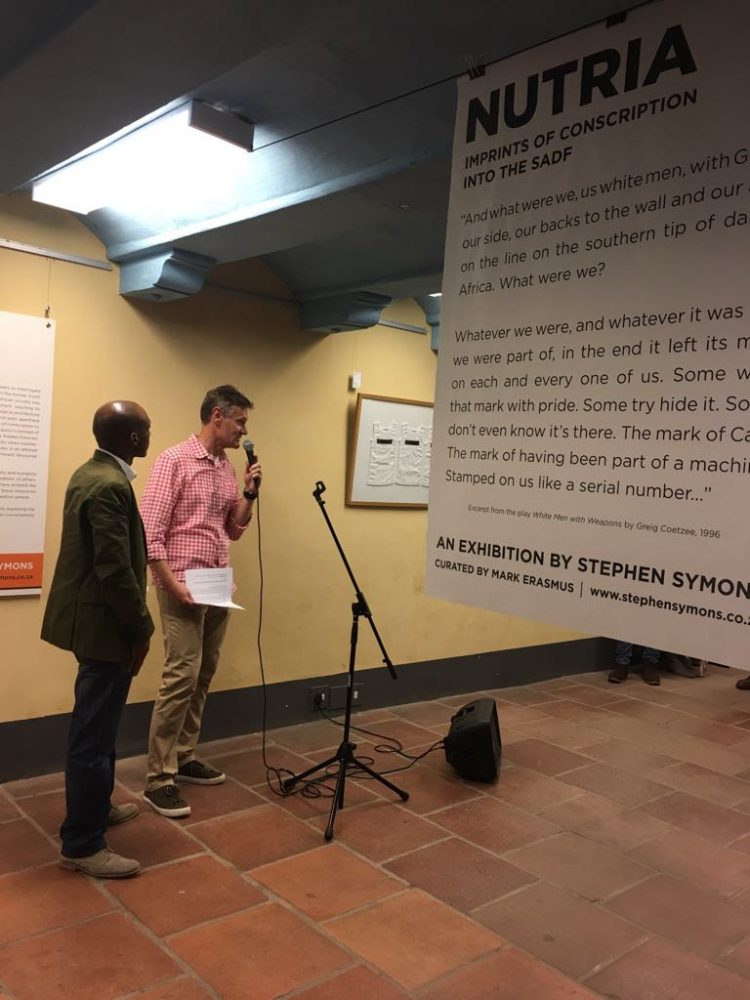

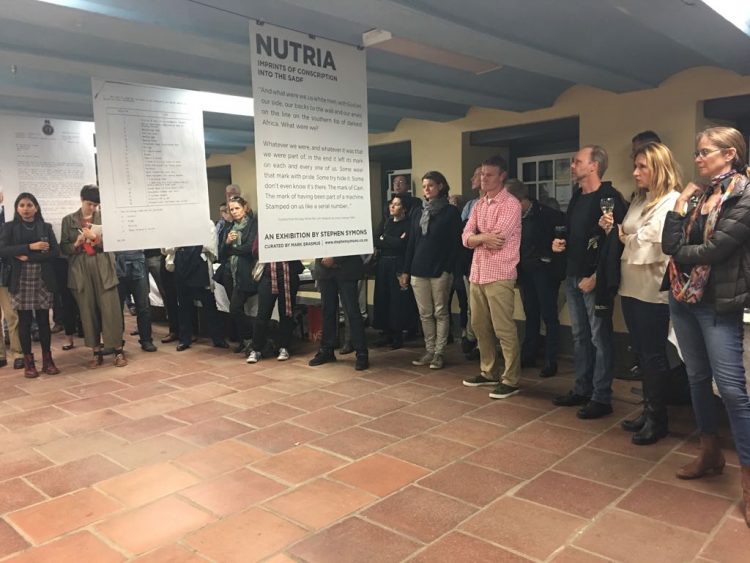

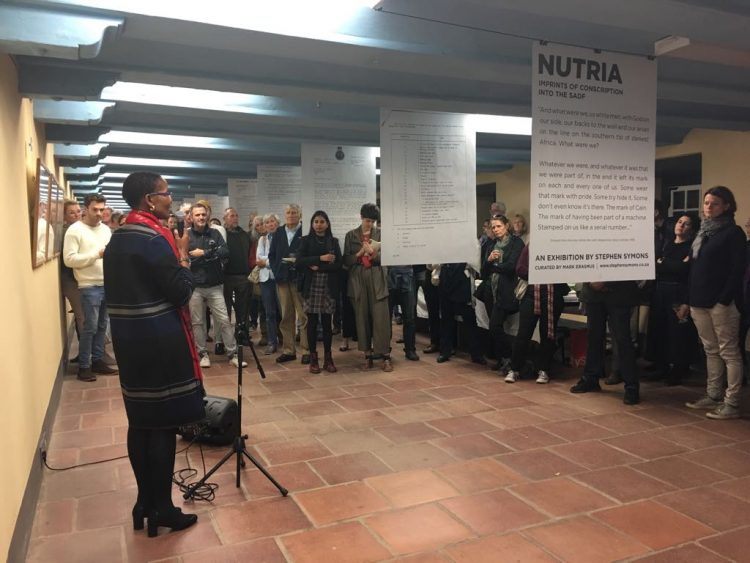

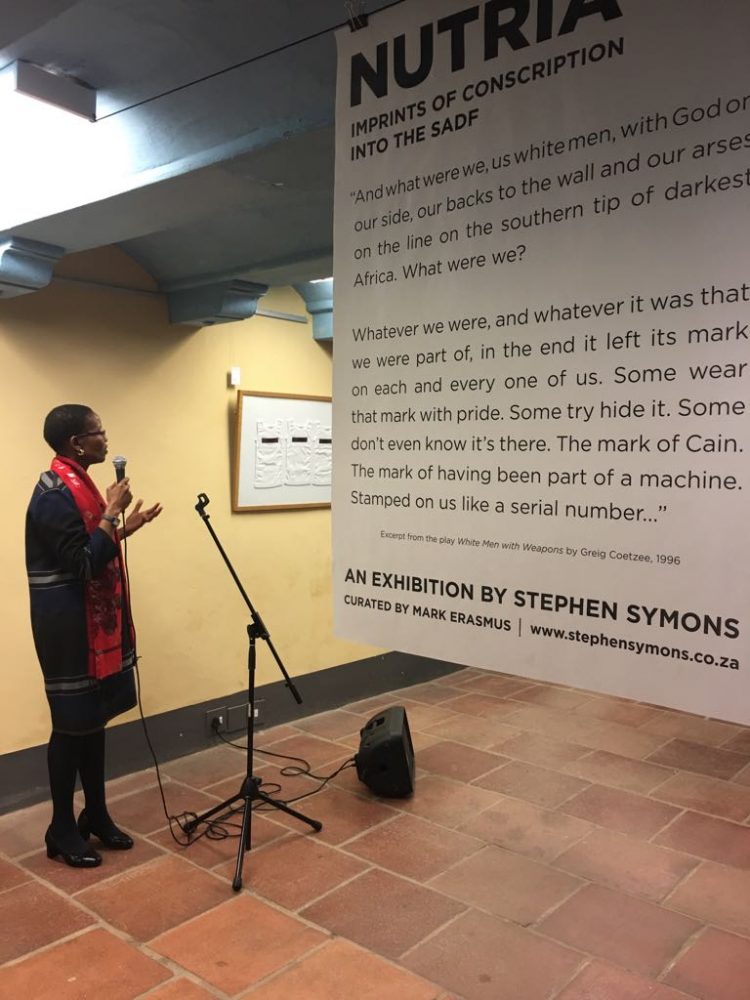

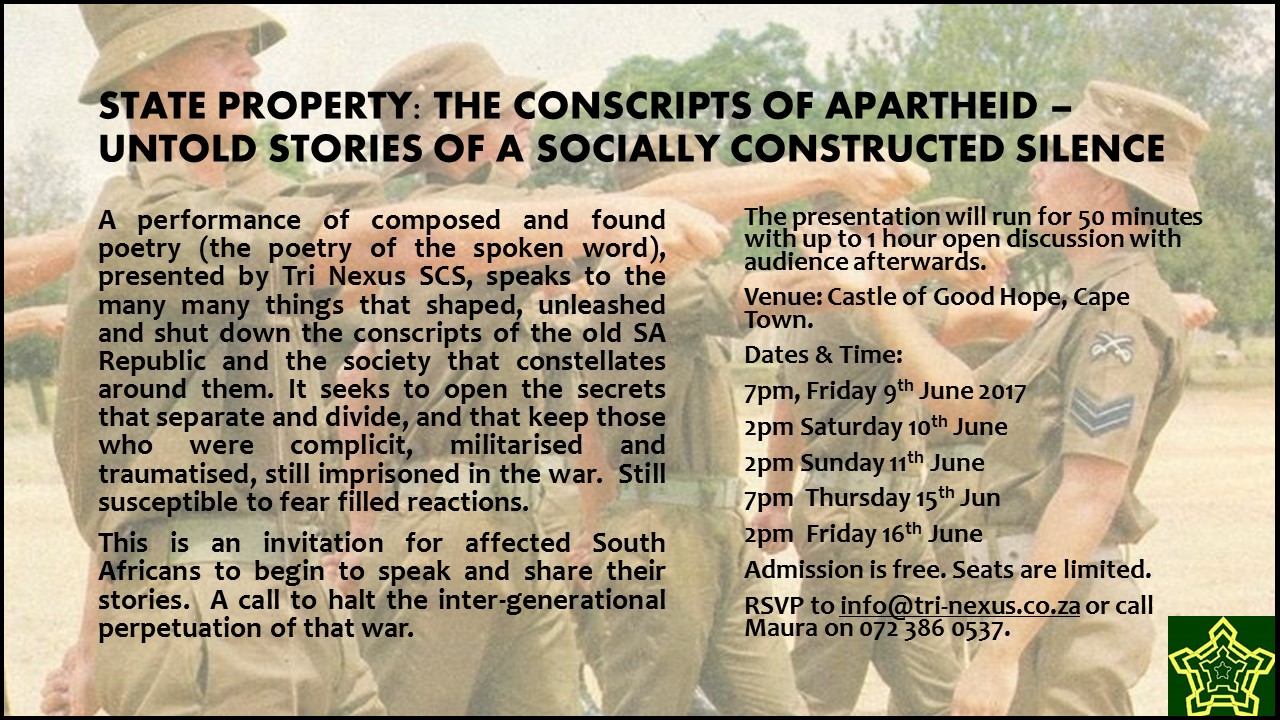

Last night I was at The Castle of Good Hope, at one time the administrative hub of the SADF in Cape Town. It was here that I attended the opening of NUTRIA: Imprints of the conscription into the SADF, an exhibition by Stephen Symons, where Professor Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela gave an opening speech. Gobodo-Madikizela, now a professor of clinical psychology and previously a part of a special hearing on conscription for the TRC, told of a time, in 1983, when she found herself in a church in the Eastern Cape, surrounded by young, white men in uniform. She got up, not wanting to worship with men responsible for her people’s pain, and, as she did so, she made eye contact with one of the soldiers, she saw how young he was and it was this that made her think “what is it like to be forced into a war you know nothing about?”.

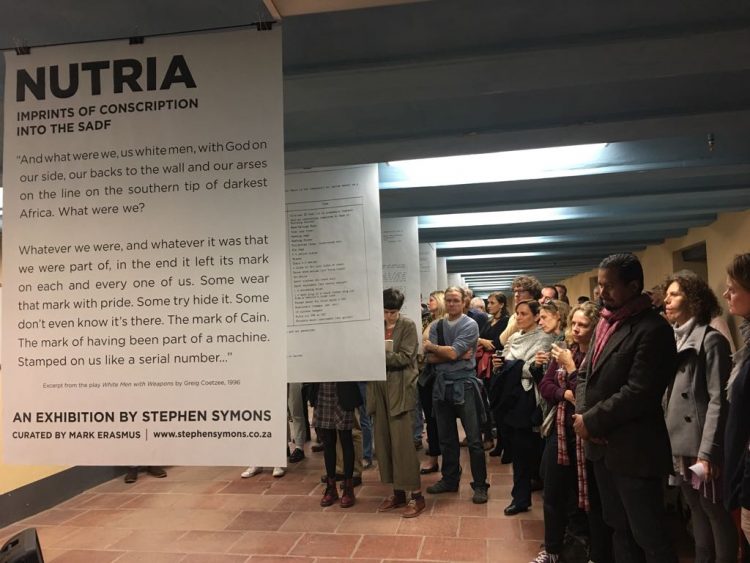

This opening remark permeates the exhibition. 660 000 youth between 1966 and 1993 were forced into conscription and many of them never speak of it; not of the violation of their youth or the things they did. It has become a part of a traumatic history that most will not confront. The exhibition addresses the question: how does one live with the acts one committed and move on? Stephen Symons, in his introduction to the exhibition, spoke of how he hopes to achieve conversation through creativity, not only about conscription but of the many traumatic histories the people of this country bare, while Gobodo-Madikizela posed the question, “if it is not articulated (or spoken about) where does it go?”. The war objects, artefacts and images curated in this exhibition tell of the stories of brutality and memories of pain while hoping to start to create a way to talk about this traumatic history.

Words by Lyndall Cain (source: http://www.cca.uct.ac.za/opening-of-nutria-exhibition/)

OTHER EVENTS TAKING PLACE IN THE NUTRIA EXHIBITION SPACE

NUTRIA EXHIBITION OPENING 5th OF JUNE 2017

'Recalling strange days of white boys in brown kit' (Business Day, 05 June 2018)

by Lucinda Jolly

March 2018 marked the 30th anniversary of the contentious battle of Cuito Cuanavale in Angola. Considered the largest battle in Africa since the Second World War, it has been interpreted variously as a defeat of the South African Defence Force (SADF), an SADF tactical withdrawal and as a stalemate.

Nelson Mandela described the battle as “a turning point for the liberation of our continent and my people”.

Cuito Cuanavale is seen as being responsible for ending the border war and instigating the peace talks that resulted in the withdrawal of the SADF, uMkhonto we Sizwe and Cuban forces from Angola and Namibia, and the subsequent independence of Namibia.

New academic research suggests that the predominant view that the outcome was a failure on the part of the SADF could be debunked

Graphic designer, poet and PhD candidate Stephen Symons was one of the thousands who were conscripted into the SADF in the 1980s.

When he returned home on weekend passes from national service, he was sometimes found asleep on the floor of his bedroom by his mother, or anxiously trying to “make” his duvet. These actions pointed to his anxiety about inspections during basic training. Sleeping on the floor to preserve a pristine bed was infinitely preferable to the punishment for a rushed job.

Five years ago, Symons completed a post-graduate course as part of a master’s degree at the University of Cape Town, titled Imagining the World and run by Siona O’Connell and Nick Shepherd. He presented photographs he had taken of conscripts during basic training.

O’Connell was impressed and wanted to know how he felt about his conscription. He said he “hadn’t really thought about it”. This set him off on a journey of rediscovering how he and other conscripts felt.

“Often these histories require a number of decades before they can be expressed, navigated, interrogated and disrupted,” he explains.

“My approach to my research is to get people talking,” he says. For Symons the concept of national service is a misnomer, as “conscription was forced and racially segregated”.

In June 2017, Symons exhibited Nutria, Imprints of Conscription into the SADF at the Alleman Barracks in the Iziko Castle of Good Hope, which has the “unsettling smell of a place which hints at decades of use by soldiers”. The title Nutria refers to the brown colour of SADF uniforms.

It consisted of 32 photographs Symons had taken as a conscript, illustrations, oversized copies of SADF documents related to conscription, including call-up papers and deferment papers, installations involving objects such as SADF uniforms, webbing and weapons. The responses to the exhibition were wide-ranging, from people finding it chilling to seeing it as a memorialisation of the experience.

The aim of the exhibition was to “address the question of how does one live those memories and move on”, Symons says.

In 2016, he attended the first symposium on conscription at the Beyers Naude Centre for Public Theology at Stellenbosch University. This was the first time white conscripts, academics, theologians and resisters had come together and spoken of their experiences. Symons’s latest exhibition was held in February at the University of Pretoria, where he is completing his PhD in history and heritage studies, and was titled Nutria 2.

Symons is particularly interested in the 1980s — partly because he was conscripted at that time and because “it marks the apogee of the military might of the apartheid regime, the beginnings of the SADF’s implosion and failures, and the increased resistance to conscription from white society”. By 1987 “the townships were aflame and by 1988 the so-called border war had reached a stalemate”.

Military service

He believes that “the silenced and largely militarised pasts of apartheid-era males is most likely one of the most neglected histories of SA”. For white men of his generation and previous generations, the military experience began long before their call-up. White males were liable for military service at the age of 17 and remained liable until 55.

Symons points out that as a result of compulsory conscription, fathers often willingly allowed their sons to be conscripted as they had no direct experience of war or the rigours of the military, unlike their fathers, who were of the Second World War generation. Most white boys had to undergo cadet training at school but the process of militarisation began much earlier.

Symons has a vivid memory of being seven years old and driving past the Youngsfield Military Base in Cape Town where soldiers were drilling along the fence line. He turned to his grandmother to ask if he would have to go and fight in the bush one day.

His research engages with “how those memories play out in a contemporary or post-apartheid space”. He suggests that “these memories become counter memories in the sense that they run contrary to dominant political discourse”.

American sociologist George Lipschitz coined the concept of “countermemory”, which describes memories that unearth the past and expose hidden histories excluded from dominant narratives.

Symons says Facebook groups, other social media platforms and blogs memorialise those experiences for white South African men, perhaps to avoid “embracing issues” related to accountability, compliance and trauma.

He says many former SADF conscripts “view those years with a tremendous amount of nostalgia and a sense of duty-bound honour. Underpinning everything, there is an obvious sense of camaraderie.”

These memories are often given voice in what Symons terms as “almost exclusively masculine confessional spaces” such as braais. In these “spaces of commonality” men can safely open up and relate.

“As a result of these largely silenced pasts, there is a sense of disconnection from the present, coupled with disillusionment and resentment,” he says.

“Former SADF conscripts felt they had given two years, and in some cases many more if the camps are included, to a system that betrayed and lied to them. Yet if you asked these men why they were there, many would say that they were there to stem the tide of communism or ‘rooi gevaar’ in Southern Africa, and still believe it.

“Attempting to understand and grapple with the silence of ex-conscripts is a highly complex space. Guilt, trauma and post-conflict silences are common factors that delay the exploration and public voicing of experiences of all former combatants, irrespective of the theatre of conflict.”

Research has shown that effects of trauma are transgenerational, transferred to future generations

The antidote to this, Symons believes, is “that by researching these histories and acknowledging their narratives, it allows other sectors of society to actually see these men, who still occupy positions of power and decision making, in a different light and to understand their complex histories in the largely contested and disparate social spaces of SA”.

CONTACT US FOR FURTHER INFO

The Castle of the Cape of Good Hope

Website: castleofgoodhope.co.za

Address: Darling St & Buitenkant St, Foreshore, Cape Town, 8001, South Africa

GPS Co-ordinates: -33.926019, 18.428091

Opening Times

|

Sunday

|

|

|---|---|

|

Monday

|

|

|

Tuesday

|

|

|

Wednesday

|

|

|

Thursday

|

|

|

Friday

|

|

|

Saturday

|

|

Stephen Symons "Blerrie Kommunis", 2017, Digital print, 79.7 cm × 59.8 cm (31 in × 23 ½ in)

Stephen Symons "Conscript portraits", 2017, Digital print, 79.7 cm × 59.8 cm (31 in × 23 ½ in)

Stephen Symons, "Rooi Gevaar", 2017, Digital print, 79.7 cm × 59.8 cm (31 in × 23 ½ in)

© 2026 NUTRIA